During the 5 years that I lived in Namibia – the country I fled to when I could no longer breathe or manage the banal and hurting commentary on my dances from South African critics – I did some interesting and very different performance work.

This performance accompanied the era of independence from South Africa. It was exhilirating to live in Windhoek. It was uhuru alive and well and in the process of radical celebration. One did not, not speak about the emancipation that was felt by all. Flags were flying everywhere, various political parties had lengthy rallies, translated by up to 9 people at a time and yet there was an air of trepidation. It could also call in a total collapse of good will. (But this was less so the case as it was in SA 4 years later.)

For me it was a ‘schizophrenic’ experience. I was not Namibian, but only a visitor to the country to learn from the process of democratization and what my role would be in it. For some I was the enemy, White, South African and not yet Namibian.

The assassination of Anton Lubowsky, a local lawyer who was an activist in the liberation struggle, marked a time when all suspicions rose high again. This was the time when I looked for psychological refuge in a workshop in Process Oriented Psychotherapy run with the title World Work, in the centre of Cape Town. The Americans who ran the workshop came unprepared for the enormity of our struggle as South Africans. The group scattered apart after 5 days, completely out of the control of the facilitators. I flew back to Namibia, rather fragmented and sad. The rest of that group re-grouped and licked their wounds, so to speak. I was back in Namibia contemplating world work on the ground and what would SA come to in the near future.

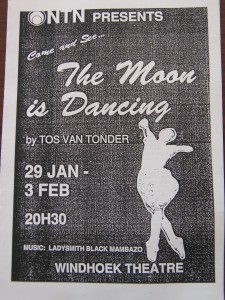

I decided to make something of my experiences. I wrote a number of stories, and tell-and-danced them to the music of Ladysmith Black Mambazo. With T-shirth, skirt and veldskoene I illustrated my dances. With specific attention to remain literal, telling stories people could relate to, and dancing with relevance to the stories, I had a good feeling that my personal renditions of my experiences was a contribution to the art world in Windhoek, which I contributed to, as South African.

This

performance took place in Windhoek only for 5 days.

Here are two stories which illustrated the era.

First dance: This is an extract symbolising White’s fears and willingness to participate in the freedom struggle. It depicts her exclusion and awkward inclusion, but exclusion nevertheless.

There was a celebratory march…an old (White) woman on the street trying to cross….

“On the pavement trying to decide when to cross the street. She looks at the procession of jumping and shouting people. Should she wait until the crowd has passed, which could take a long time, or should she cross the street now? Meantime the crowd is coming down towards her with increasing energy. On several occasions she decides to put her foot into the street, each time changing her mind, heaving her body back onto the pavement. At one final point she make the decision and steps courageously into the street, precisely when the crowd was a mere arm’s length away. Her weak legs give way under her. Faces! Buildings! Colour! Victory! Her body slides to the ground in a slow fall. A man emerges from the crowd and swiftly without changing his movement or his rhythm sweeps her from her feet and places her back onto the pavement. Then he re-merges with the crowd which continues seemingly unaffected down towards the sculpted kudu in John Meinert Street.”

Last dance: This is an apocalyptic version of Africa becoming free. It shows in the flags, in a conversation I have with a man, in the manner in which the skies move, etc. It takes with one the idea of a dance of hope, but assisted by the apocalypse to do so.

The crowd of little flags silhouetted against an apocalyptic sunset. Behind me the men’s single quarters, people cutting and stringing raw meat in little stalls. The ground abuzz with pre-election excitement. From quite far away I see a man who is seeing me. He is walking towards me at a brisk pace. As he nears we both extend out arms. He has a happy, open face. I find myself saying: Wat dink jy? He turns, shift his feet to gaze with me and then says: Dit gaan alles regkom. Ons moet net mooi trap. Sometime later I find myself on the edge of the township, looking at the hills that surround this town. Heavy dark clouds were stacked in the west, leaving a clear strip of blue sky between them and the horizon. As I stand there I see the moon, full, raising herself, slipping up, into this clear strip of sky. She is powerful, strong, light! Then she disappears up behind the clouds. About 10 degrees still higher up the clouds moved, transforming themselves until they break into a piece of clear blue into the shape of an….arrow – sharp, clear, pointing south. And then, up into this arrow space arrives the moon as if with a clear purpose to illuminate. Was this a sign? A miracle even? Still there was something inside me that didn’t want to believe this. Did anyone else see this? Or was it only visible to those who wanted to see it? Behind me the sun had already made its exit. Music from ghettoblasters were faintly audible and dim streetlights began to dot the township.”