The restoration of white integrity in South Africa

The controversy of what it means to be South African is a complex and even highly contested topic. The diversity that we are as South Africans vary from the ease with which one can buy yourself into status, to the identification of being South African as being the one who feels that all that will go wrong will be blamed on Whites, something that Whites would never be able to refute, as sentence uttered by Antje Krog in 2015. Whichever way, identity has a deeply emotive charge around this question: who is a South African?

It would take a long time to explain this to a person who has the tendency to counter every stance of SA identification merely as a sparring exercise. This is not what I propose here.

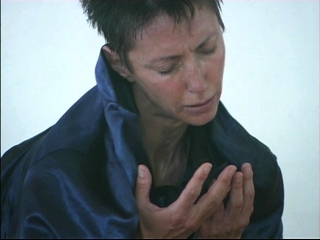

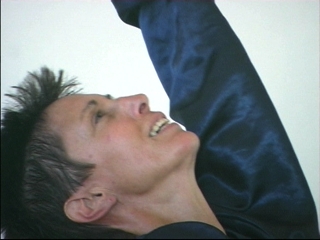

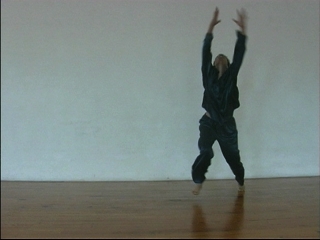

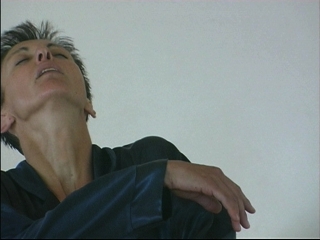

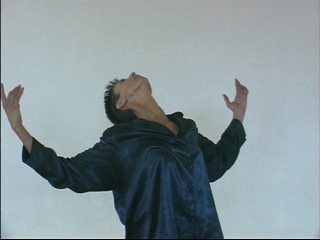

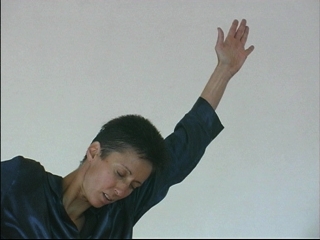

As a dancer, I believe that we incarnate all impulses into our beings and bodies in a visceral manner. The art of the dancer who listens for the dance, is to detect what it is that we carry around with ourselves, where it belongs, where does it come from, how do we embody this?

When I think of SA, I become heightened with a feeling that is charging me within.

It is advisable to not fling oneself into the plethora of the daily news, but rather to collect within oneself the soul of ‘atmospheres’ , moods, pertaining to the subjectivity, the nature of South Africa at that moment.

The exercise combats the incessant need to counter that idea with another that would be ‘in competition’ with your image. This is not uncommon. Sit with friends discussing SA and you feel like you experience a see-saw effect of arguments.

This is normal to the psyche in perpetual flux, in constant reach of a stable identity. Living in SA asks this of us, namely to constantly consider another option, another socio-economic facet of the argument, yet another political stance, in favour of a particular racial group. The drama is endless.

But for the art of embodying SA, a discipline to capture a moment that one anchors as your truthful perception, before it is being challenged, by no-one else but yourself, you need to stay loyal to your image. For a painter this would be the normal run of the mill practice. You choose your subject matter, get art materials that compliment your choice, and you perfect the image.

In movement this is different. Your body takes a snapshot of your image, in a gesture. That is only the start. From here onwards, your palette is your personal history, your bewildered dreams, your fears and your shames, your terrorized flashes of survival, your compassion for a victim, being overwhelmed by glory, fascinated by miracles, drenched in sorrow, disconnected from besieging images on every corner, demanding our attention. And White guilt.

One has then moved beyond one’s own canvas, but one is still embodying South Africa.

This is not a predetermined and neatly structured choreography. The discipline of being in the moment whichever way you move, and that this remains connected to the revolving image you hold of SA, is the art.

This genre could only be performed by established and well-rounded practitioners of the theatre. Technically and mentally this discipline is demanding and a personal history of thorough technical explorations is necessary to bring the aesthetics of this work into the moment. It is a matter of knowing your craft so well that you could discard it in the service of the best aesthetic of the moment, with whatever it takes.

The aesthetic aspect of this work is inventing itself as the performance is being conducted. A strong awareness of what is being created and how it lands in the body, deeply loyal to its interior component or image takes discipline.

During 2001 I collaborated with Francois le Roux on a production called OPUS. The name called in the magnitude of the undertaking for two performers to be loyal to the image that each created in the moment, yet the dance and the cello still had to find points of reference that would enhance the final product.

It was turning the self inside out, with whatever contents it brought into the frame of performance supported by a deep listening to the fellow performer, the voice productions, cello and dance.

Four performances were held in the studios of Jazzart Dance Company, even though the company itself had moved to the larger premises of Artscape at that time.

The performance was also included into the KKNK Festival of that year. It was placed in a large school hall. Not many people arrived. I remember an elderly couple, the man was blind and the woman spoke softly to him about what was going on, on stage. She spoke incessantly. It touched me. They came to us afterwards to congratulate us. It was the family Kingwill from a farm in the Eastern Cape. Strangely, we bump into each other often in the most extraordinary places since that time.