It was during the years 2004 onwards that I had a distinct feeling that my body was aging. It made specific demands on how I began to think about myself. Whereas I experienced my body as ‘whole’ on my mind before, moving in one piece, everything coordinated, nothing left out of the frame, so to speak, I became more aware of different parts of my being. One hardly knows that one consists of body until it falls apart.

James Hillman the Jungian, in his book The Force of Character in the Lasting Years compares this stage as that of a sock. You are made of the same sock, but it is becoming frayed and holey. You need to look at the holes and concentrate on darning every hole as it comes into your vision. Ultimately you are still the same sock…

Even though the material is different, you will retain the same form. Form individualizes. Form has an active force. The new wool must become me. The afternoon knows what the morning never expected.

Photo: John Hogg

Aging is the grand confrontation, the coalface that nobody escapes. You have a set of attitudes and interpretations regarding the body and mind (may the two never let go hands!) that suddenly outlasted their usefulness and youthfulness.

One’s character is one’s inmost nature, but its underlying nature remains a mystery. What is healthy for my nature is healthy for my character. Collectively this aging represents companionship, freedom, all the arts, silence, service, simplicity and safety. One’s interest shifts from information to intelligence.

Symptoms give form to character. It forms the vehicle of reaching the other level. Wetness make place for dryness. One must dry out the freshness of naïve enthusiasms and overflows of sentimentality. The dried soul has a dry humour and a dry wit, a dry eye that sees the world with less subjective affections. We become astringent – sec, like good wine.

The body, even when coming apart, even if ruined, knows what it is doing and relies upon an archetypal reason, which gives it its wisdom. A symptom suffers most when it does not know where it belongs. There is myth in the mess. On the scale the heart balances the feather. That is the work – to do something for no other reason than for its difficulty. Thus to overcome the heaviness of heart.

Photos: John Hogg, & My Father

So what is left after you have left is character, the layered image that has been shaping your potentials and your limits from the beginning. When the body breaks, the habits of conformity and character come through the cracks. Shame, guilt and low self-esteem are necessary to character formation because they eat away at innocence. Shame is one of the gifts reserved for age. Suppression of the undesirable goes only so far and lasts only so long; then the repressed returns with a vengeance. The force of character is those traits you can’t fix, can’t hide, and can’t accept. Character is my courage, my dignity, my integrity, my morality and my ruin. Character does not appear in psychology curricula. Your history must me personified. Character is a psychosomatic idea. It comprehends psyche and soma. Character is not personal. It is an imaginable description.

Elders make higher evolution possible, can see the angel in the child, and its calling. Inspiration belongs to grandparents and inoculates the child against paranoia. Grandparents’ character can shelter a civilization from its own predatory frenzy. Grandparents raise the voice from the trivial and personal to the cultural and the important.

Youth is an individual calling. Age is character. It gives sense and purpose to change. Character is a therapeutic idea.

Our greatest endeavor is to make ourselves irreplaceable. No one else can fill this gap that will be left when we die. From profane to sacred, from thing to image, from useful gadget to useless art.

Photos: My Father

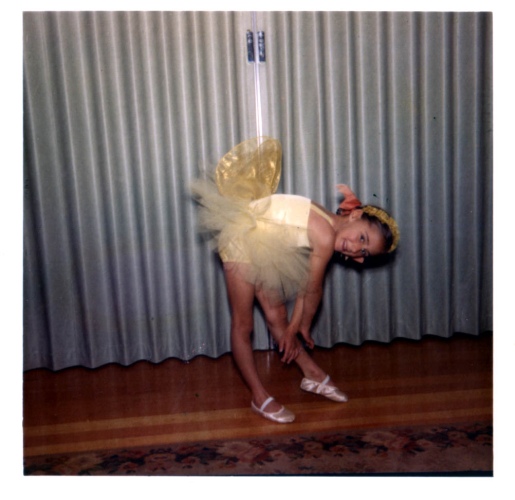

alfabet was created to respond to this change in myself . I also wanted to gather everything that belonged to my dancing life and bring it onto the stage. It consisted of all the costumes that my mother had made for me as a young child. I decided that they needed to hang at different heights to indicate the size of the child within.

Then Luyolo seemed to be interested in this exposition. The whole house was taken over by the volume of costumes hanging against the walls, draping over the sofa and so on.

In time I was busy with the idea of what the mark was that I would be leaving behind; what would be the legacy that I leave? The idea of marks on my body, not as tattoo, but as legacies, parts of the character I am came to the fore.

By then Luyolo had been filming many of my rehearsals at home and the question of what to do with the marks came up. Over time he became part of the performance. He filmed the whole performance, stopped me at the height of my characteristic exclamations by putting his hand over my mouth, undressed the ‘bag-lady’ costume with all my dance medals on the lapel, allowed me to fall back into his arms and began to trace the marks on my body while filming himself doing this at the same time.

Then he left the camera on the floor over me. He took one of my childhood items, a red tap shoe, listened to its clack and walked off stage with this sound, while photographs of myself in childhood costumes would be projected onto the screen above the performance.

We did this performance at the Intimate Theatre in Cape Town and were then invited to the Dance Umbrella in Johannesburg.

After these events I began to prepare for a cremation of all the costumes. This is a statement about having ceremonialised my mother’s labour, having left her house, having instated myself as mother, and celebrated myself as aging dancer. The cremation took place in my fireplace at home.

Photos: John Hogg