During 1983 I came across a photographic exposition of David Goldblatt, in his book called In Boksburg. It spoke directly to me. It depicted the milieu, affinities, circumstances and pathos of a South African middle class White community in the suburbs of the Witwatersrand, in this case Boksburg, a mining community on the East Rand, an hour east of Johannesburg. It could as well have been photographs of Afrikaners (which is how I interpreted it when I saw the book the first time) from the mining town of Carletonville, where I grew up, one hour west of Johannesburg.

The fact that Goldblatt took these photographs, in the first place, was comforting, culturally affirming, even though some embarrassed me. Some got just too close to the truth of the shame and pain I felt about the Afrikaners, and about being an Afrikaner, even though for him there was no distinction between it being Whites of any particular cultural group English or Afrikaner. “It was the most difficult thing I've done precisely because this was so close to me,” he wrote to me three decades later.

Back then I reckoned that he must have seen something of value, or even beauty in the choices that Afrikaners (then, for me) made at that time. And, the fact that he captured these in some odd way - not necessarily posed, perhaps the moment just before the moment when the subject wanted him to photograph what they wished him to capture - made me fonder of the Afrikaners, as subjects of artistic enquiry. They had a life worth capturing that was more interesting than casting them as masters of apartheid, or people who had a dogged existence, unaware of the material choices some began to make that would soon coin them to be ‘White trash.’

I studied these pictures from my own copy of In Boksburg for a length of time, assimilating the structures and pathos in the images, and I began to develop an understanding of Goldblatt’s choices. There was something else that I then realized. The original sense that he was ridiculing my people was replaced by a sense that he would have compassion for them beyond their understanding of themselves at the time. This perspective allowed for an objectivity that began to move the dancer in me to see this as an opportunity for a performance-interpretation of the images.

I hired one of the venues at The Market Theatre in Johannesburg, put all the pictures from this book onto slides and projected ten or so per performance.

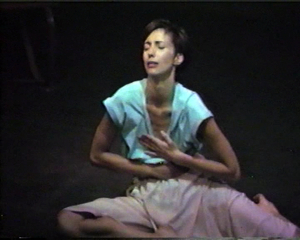

It was November 1983. I had just cut my long hair and had a hard time getting used to the lack of weight that hair adds to movement. But strangely, during this performance I began to like the crispness of movement that jutted me into an emotional movement vocabulary during this work that was often surprising.

This was pure interpretation of the photographs in the moment. A dance came from the moment when I saw an image on the screen at the back of the stage. I internalized my first response to an image and simply built out the sentient-image of each photograph. I then continued to get ‘behind’ and ‘under’ the direct impact of the image upon me. Choices of movements, enactments, pure reaction and often humour, lasted any length of time. I moved strongly in the direction of distancing myself from the sentiments I originally held towards these images. I began to explore the folly of being White, suburban, strangely content with the self, yet with immense restlessness of materiality…all visible in the faces and gestures of the subjects. I wanted to extract those new discoveries into my movement, my body and my feelings even when I was superbly aware of a deep respect I carried for people with their history, confusing politics, fear, threat of black majority rule and its denial.

I decided to title the performance Boksburg, O Boksburg. It did not occur to me to call it anything else. Some people came all the way from Boksburg to see a rendition of themselves, in performance. It took me a whole week to work myself through these pictures. One evening a theatre light burst and scattered glass all over the stage. Those things happened.

For the continuity of attention and to sustain the project of improvisational interpretation of a visual image, I chose the Tehillim Psalms by Philip Glass. It was played on cassette tape. I knew when one side of the taped music came to an end, heard the mechanism click, the technician, Martin Voges, opening the lid and taking out the cassette, turning it around, placing it back in the slot, clicking the lid back and pressing the button, to play. The dance continued all along, uninterruptedly.