UNCOMMON GROUND

at

THE COMMONS in MUIZENBERG

ARTVARK GALLERY in KALK BAY, CAPE TOWN

STANFORD LITERARY FESTIVAL, Overberg

and

"Exuberance: A Homage to Jay Pather"

a contribution to this event at UCT.

July – October 2025

By Sandi Sijake and Nobonke van Tonder

What can we know about what keeps us alive?

The limitless present in mourning and longing as

the ethics of aesthetics.

Inventing the theatre format for the uncommon, more-than political practices of love – unusual, unknown and perhaps yet unfelt by the body – for a country and its people.

The UNCOMMON GROUND performances were embedded in two peoples' lives:

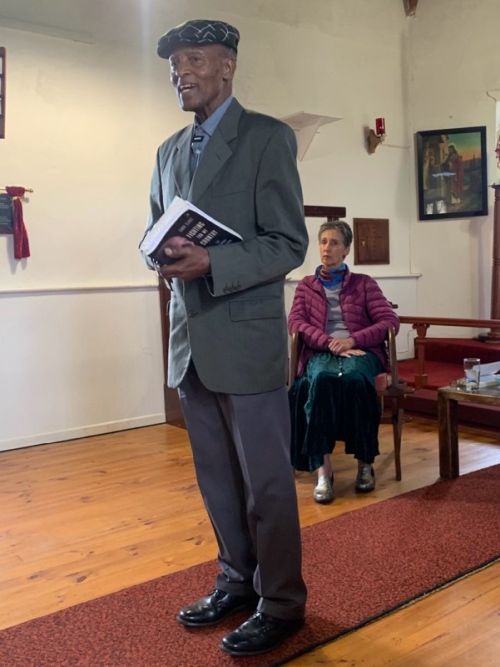

The first is the political struggle for a democracy during the decades of 1950's-1980's. This narrative is embodied by Sandi Sijake in his book Fighting for my Country ~ The testimony of a Freedom Fighter.

The other narrative – and interior excavation of political love through a maternal and subjective exposition – is by Nobonke van Tonder in her book A POLITICAL LOVE ~ The Body Speaks The Soul Knows.

The more-than-relationship between Sandi and Nobonke spans from 1991 to the present. Both had left South Africa for South West Africa in 1988. Sandi, newly released from a fifteen-year sentence on Robben Island, found himself once again confronted by apartheid and chose exile in SWA. At the same time, Nobonke, then in Johannesburg, felt the deadening weight of political perplexity in South Africa and turned to SWA to pursue her psycho-political interest in societies moving into the post-colony. It was in Windhoek that they met. A few years later, Nobonke became pregnant, and the couple returned to South Africa, where their son was born in 1993.

The Books

The two books arose as necessary acts of remembrance, each tracing the contours of a life shaped by struggle and transformation. Sandi's book recounts his early years in the ANC, his military training in Africa and the Soviet Union, and, upon returning to South Africa, his arrest and 15-year imprisonment on Robben Island. In essence, it is an autobiography that concludes with his release on 18 June 1988. Nobonke's writing, by contrast, turns inward: the intimate world of a woman pregnant during a time of profound political transition. Her work explores how these shifts took shape as political dimensions of love, as well as in the near-ungraspable, silent language of a dancer's body moving through radical transformation in the presence of a freedom fighter.

As the two writers presented and reflected on their books, it became clear that the confluence of their stories – shaped within a more-than-relationship of 34 years – formed an event of larger embrace, one that held both the vast sweep of the political movement and the intimate currents of personal movement within their two bodies.

They began presenting and reading from their books in various settings. The first was as guest lecturers invited by the Drama Department at the University of Pretoria. There, UNCOMMON GROUND unfolded as students and authors swam together in an ocean of stories without predetermined theme or intent. Much of the dialogue was driven by the students' questions about the authors' lives. These exchanges ignited reflections on the students' own identities, politics, bodies, relationships, and futures, as well as their curiosity about the unlikely pairing of a white woman and a black man – two individuals from vastly different backgrounds with seemingly little in common. Yet from this relationship emerged both parenthood and artistic creation, illuminating the vicissitudes of complex lives lived in a country where politics permeates every gesture, image, and conversation.

The energy released from this first encounter – and the possibilities it suggested for future engagements – encouraged the authors to create further public events. One such space was The Commons in Muizenberg, a local bar known for poetry, music, talks, celebrations, and dance. Over three consecutive weeks, they appeared one evening per week, beginning with simple readings from their books. Gradually, these evenings evolved into a fusion of text and movement: silent exchanges between their bodies, accompanied only by the sparse, slow piano, an audio recording by composer Nils Frahm. Their interaction drew on impulses of touch and listening, echoing the dance form known as Contact Improvisation, where bodies remain in direct relation to one another. Yet this was no polished practice—it was a raw, exploratory dialogue between two authors, unfolding live in the presence of their audience. The response it evoked revealed the potential of this experiment to stand as performance in its own right.

At the success of this exercise, they decided to approach another venue, this time an art gallery called Artvark, in Kalk Bay, Cape Town. The historical gallery was a parson's home, built next to a similar dwelling, the then church and has a wall dating from 1880, in the, then, parson's home, now art gallery. They decided upon this 1880-room as performance space where they would ignite the feel and experience of theatre. They brought on lighting and sound and began to prepare their reading along certain themes such as

unravelling illusions

shocking surprises

journeys and destinations

parental wisdom

sudden awakenings

intrigues and betrayals

enigmatic visitors

and spirited confessions.

Audiences soon grew accustomed to the idea of theatre within this gallery-restaurant, where each evening began with sherry and ended with soup, offered at R100. The authors then added an additional R100 to the ticket price, framing their appearances as theatre performances in their own right. What began as an experiment developed into a rhythm of excellence: audiences multiplied over the three weeks, drawn to the unfolding collaboration between writers, performers, and the gallery itself. The two authors had, by then, become actors, dancers, readers, and conversation partners, weaving together their most poignant life stories. Themes drawn from their books – interpreted differently by each, personally and politically – kept audiences suspended between polarities of meaning. To bridge this divide, they turned to Contact Improvisation in its truest sense. The sight of a 70-year-old veteran dancer and an 80-year-old freedom fighter moving in embodied dialogue touched audiences deeply, stirring responses across a wide spectrum of emotion.

By this time, UNCOMMON GROUND had been invited to the literary festival in Stanford, a small village on the southern coast of the Western Cape. In the St Thomas Anglican Church, the authors spoke on their chosen theme: what it means to write, where inspiration arises, and why writing is a necessity. Sandi recalled his memory of Mrs Thompson, an English teacher at St John's College in Umtata, whose animated passion brought alive the vicissitudes of human action across territories of domination, power, and humiliation. The emotional turn she sparked in the 15-year-old, life left a lasting imprint on his ability to embody a story. It was one of many influences that eventually led him, a decade ago, to write Fighting for my Country.

Nobonke's reading turned inward, reflecting on writing itself. She shared a journal entry from 1993, written during her pregnancy, when she realised that her vivid and detailed accounts of life might one day take the shape of a book. This recognition drew her writing into radical depths, including an imagined dialogue with her unborn child about relationships, politics, her transforming body, and her shifting role – from daughter, to mother, to partner of a freedom fighter.

Both interiors are complex, potentially brittle and by necessity resilient-in-the-making, perhaps a justice-to-come. Both role players have South Africa's future foremost on their minds, but perhaps in different ways. For Nobonke the frame of a functioning country is crucial for her role as mother. For Sandi the freedom of black people from colonial domination has a different picture, albeit not clear on the ground. Yet, they depart for South Africa when Nobonke is 7 months pregnant, an event which ends her book, one seeped through in spaces of the future imaginary for the reader.

The Dance

For further reflections on UNCOMMON GROUND, we now turn to the dance. Yet it feels only fair, before doing so, to pause and share a few considerations. These events were never staged without serious contemplation of their ethics and how they contemplated the notion of representing the other, and how the dance became a presentation of its own evolving genre.

From a relational perspective, Sandi and Nobonke recognised that their role was, in part, to shape encounters with the hope of bridging divides – perhaps many, some still hidden. What could not be achieved in writing might be revealed in dance. How would the political love that Nobonke traced in every intricate micro-moment – from pregnancy to expectations of the future in SA – meet the political movement of liberation embodied by Sandi? What radiates beyond the page – resisting capture in words – that might find expression in the immediacy of theatre, embodied in real time?

The moral force of UNCOMMON GROUND flows through the lives of Sandi and Nobonke, reaching toward the future of South Africa and resonating across every public encounter – between them, and between them and their audiences. As performers, they carry a profound responsibility: to remain attentive to how their presence might ripple through others, even while the precise effects remain invisible, unknowable. In dance, this responsibility becomes tangible: each movement affects the witness, and each witness, in turn, shapes the dancer. Here, the political love Nobonke traced in every intimate moment meets the liberation Sandi embodies, creating a living, breathing miasma of emotional and political intertwining – an exchange that defies conceptual capture and cannot be taken for granted.

The Origins

The movement that these writers embodied was present from the very first year of their relationship. Then, as now, much of what could not be articulated in conversation found expression through body movement. The sheer physicality of this relationship – played out in open spaces where movement could unfold without constraint – was a feat in itself. These explorations took place in backyards, on desert plains and dried riverbeds, among dunes, and within the intimacy of their home.

Swakopmund 1992.

It is one thing to hold in the mind the concepts of multiracialism, cross-gendered existence, multimodal political ideologies, the post-colony-to-come, and divergent visions of Africa's future – but quite another to live them, to let them pulse and move in the most immediate, material form: the body in motion. Such embodiment demands a radical rethinking of relationality from perspectives that are more-than-available. What comes forward, and what recedes, as the eye turns inward and outward, tracing the self in motion?

In posthuman philosophical terms, one could say that they each had to diffract the relationship through itself – through its personal and political milieus – as a unique labour of gathering, collecting, selecting, reviewing, revisiting, re-turning, refuting and moving their bodies as the very essence of performativity. "We do not move as two people, but as a myriad of meanings influencing the room, its people, the history, every stone and its labourer, the past and future enfolded within each move, and its silence," writes Nobonke.

The Poetics of Silence

Nobonke: "One could probably say that the most poignant moments of the dance involved the silences. These moments still the image for us and for the observer, allowing for a depth to be attained in the consciousness of everything present. We are also stilled by the presence of histories in the room, ancestral presence and honouring the immanence of stillness itself. And we honour our bodies' intelligibility to sense the immanence of the fullest, or the void of existence. We sensed that silence is full or empty. Yet, we must hold all these possibilities, and more. To see silences in both movement and attention, we are all in the process of creating an art form. To feel silences, may also offer an opportunity to audiences to be drawn into action: psychologically, philosophically, emotionally, intellectually, politically, and spiritually. Just as a reader sees unwritten parts in the text, the onlooker, senses the unmoved parts as eliciting significations only they could have access to, albeit momentarily."

Silence in the dance, happens to dancers. It may open the questions surrounding the movements that did not happen to the dancers. By now the silence in a dance between the two dancers of UNCOMMON GROUND, reveals the grounds that may also not have happened yet, if ever. Largely differently from what is not written in a book, what is silent in a dance is immensely present – as felt, witnessed, embodied, emoted, insighted and en-spirited. However, largely differently from what is written, the dance may hold speculation for the spectators, but rarely for us dancers. The sense of an ethos is far more rivetingly visceral and unavoidably so, than that of the word. Still, we cannot and do not know what is happening in the silence. The dichotomy of ‘right' and ‘wrong' as largely present in literature, is absent in the dance. Elimination of the binary as it happens, as the dancers, calls in the imagination and ‘dreaming' for the witnesses free from some of the most dominating thought forces in our conceptual activity in human history.

It should not be forgotten that silences are present in their books as well. While the density of politics and interiority sustains the ardent passion of their writing, the dances of their stories – and of lives – find their fullest presence in movement, revealing themselves in the encounter with something spiritual, something they must surrender to, for lack of a better term.

Nobonke: "Altogether considering what we do not know in the silences of our dances, we could only ‘advise' witnesses to not engage in hardening mental labour, extractive meaning or enforced thinking towards greater affective ease. The dance spirit migrates in the room and enters all (and everything) in its presence. The body may not understand things, but it does feel that moment. To allow this feeling its rightful place, would be a device to meet the dancers where they are at, and how their dance affects witnesses. Beyond the binary of ‘right' and ‘wrong', we are all in the beckoning space of the unknown, becoming art ourselves balancing information with the lack thereof."

"In writing through this work, I attended to the details of the undertaking – its complexities, agreements, engagements, and outcomes, which often generated further complexity and demanded reconsideration. I knew that troubling UNCOMMON GROUND – diffracting UNCOMMON GROUND through itself – is not a linear process, would generate multimodal theoretical frameworks, different slants on knowledge of this undertaking, and an augmented relationality in the making. In true posthuman terms I and hopefully we, were embodying a performance of justice-to-come, beyond our sense and knowledge of justice per se. With the documentation of UNCOMMON GROUND in October 2025, this account escalated."

What do we do with that?

"Complex thinking will not allow you to stay within the circle of one discipline or one culture, one era, one ideology, one psychology or ontology. Politics, sociology or psychology has never solved a problem on its own, unless you want a thought turning around itself. At best this event of Sandi and myself, plus our books, our parenthood, our age, our still deep entanglement with post-liberation, post-colonial South African politics and our manner of embodying performance with our bodies form a narrative matrix.

Each UNCOMMON GROUND event gathered its own intentional power in which I felt caught up, bait for the intentions I was making my own. No doubt this is more often the case than one imagines it to be. It is a strange reversal of will, not letting go of something. In fact, letting something get a hold. It's a different thing altogether."

Not without the dark night of the soul.

"But in the interstices between performances I was in pockets of the dark night of the soul. I posed myself serious questions. What was I taking for granted, what was I appropriating about Sandi's life for my quest to bring a different channel into UNCOMMON GROUND such as performance, and specifically dance? Was his book and story not to stand on its own? Or even my book in that case? Was I not clutching to theory of performance which may bring a perverse slant into our stories of struggle? These are questions known amongst white explorers in the post-colony, by the way, as the colonial thrust of our history is deep with numerous perspectives often unexplored and interrogated. But was I attaching capacity to Sandi that he would not wished to have had? Was I dominating the stage with a known embodied presence of performance in this manner? Are we dispossessing each other from the sovereignty of (post-colonial) existence by offering its embodiment? Is there a narrative space for resistance in this project? Have a failing state not expropriated our sense of body, work, land, language, safety, well-being enough? Would it not be better for the books to stand on their own, with extreme difference in genre and history, politics and psychology? Was it fair on us to expose ourselves in this way as elders? Take note, that these were questions I dealt with intimately on my own. This was my liberation towards which Sandi was making a contribution. What of his trajectory was for himself and not known to me at all, yet trespassed and trespassing incessantly? Was his participation conducting the same acts towards me? Were we fetishizing each other publicly? Since the body is never dissociated from its deep past and history – an extensive territory, as an expanded matter, that sets in relief some corporeal knowledges, which are in turn territories of alliances – what is the territory of touch and its transformative potential, and how much of this lies outside the awareness of participants themselves? Was I conducting this project with maternality, relationality, partnership, political, spiritual concerns?"

The Dead

"A relational and holistic entry is what I aim at in this writing. It includes death, the necessity of embodying our legacy, something that is to be followed through by way of making stories, iteratively through the knowledge that any act could be our last. I realised that this process would have its own coherence, that would not be known and knowable to me – or us – at any given moment. And it is precisely because of the presence of this immediacy of being that an ontological tact was required".

"Because it is the dead that is present in our past lives, our ancestors, the stories past in our books, the death of a moral substance in our government, having had outgrown our usefulness coming from an analogue world, subsumed in the digital, cyber acceleration and knowing well that all that cannot be captured is how we are in the moment."

"In the stream of explorations of human responses to changing times, the popular notion is that humanity could be expressing two major emotions and their fringes and overlaps with other emotions, namely longing and grieving. Considering our ages, we could be standing at the edge of our own lives with variables of these two emotional states, anyway. Change is simply augmenting their presence multifold. This occurs while the dead and the living continue to interact and affect each other profoundly and productively, under all circumstances, which is why there are rich vocabularies, striving to express these relations."

"This event is in the depths of finding, uncovering, excavating, even concealing, masking, yet troubling the processual telos of UNCOMMON GROUND. One may even wonder whether our books were not perhaps written to the dead – parents, families, communities, leaders, early years, values, ontologies and a dying country – differently from what we imagined, desired, hoped for and tasted only briefly. Or are our book the last straw that would give us life? A longing for a live memory? Or death as something that opens onto nothingness, that we could articulate mostly through dance's silence, stillness. Or that the dead have no existence except in the memory of the living and that it is our duty to keep that memory alive. That we would not forget what we envisioned as a future. Or that the dead is only really dead if we stop engaging with them, that is, looking out for them in our stories. Or that the event and all its work is to care for the dead. Or that we assist the dead through the activities of UNCOMMON GROUND, helping them to become what they are whether it is a soul, a work of art, built down characters led toward a new way of being by those who take on the responsibility through a series of trials that will transform them. Or the dead, they want to be forgiven. Or tell them things about ourselves that we have expected others to do on our behalf. Or with the help of the dead, act retroactively, to reconstruct the past, actively, to open up other possibilities in the future".

We are not alone

"I have a distinct sense in the dance that we are not the sole creators. The extreme slowness of dancing, a deeper listening, ignites the eternal life of the "work to be done", an unquestioned devotion. I am also aware that the dances may remain in the witnesses' lives, even after we have gone. We make ourselves capable of replying to what is being asked for, now taking on a performativity – responsibility – we could consider calling art, a fluid concept without knowledge of what is to be achieved. I also have a distinct sense that ancestral agency moves us, into the place that has been made for them to finish their work through us. And how we make choices through our conversation-reading-performances is an ancestral response to heighten the spiritual work through our visible lives."

Since the nature of our planet is with us, the same gravity and gravitas of our ecological condition, UNCOMMON GROUND have responded to the needed respect in the continual creation of an association, any connection, any relationality that is timeless. UNCOMMON GROUND is a continual accomplishment of our response to our world."

Laurie Anderson said: "If I had to choose between something that was true or something that was beautiful, I would choose the beautiful thing ... because it's more of a visceral and sensual scene ... it's something you feel rather than what you believe."

Nobonke: "I love the lack of conclusions. The simple possibility that we are in the making of some justice-to-come."

"If we look at ourselves as a milieu, an ecology, and then as a legacy, we would ask a question as if to a bereaved: where are they now? If, at our age, the "here" is emptied out with history, what is the "there" of our existence? We are working on the task of maintaining a relationship with the dead: the ancestral urge to fulfil our soul work, and maintaining the place-making of the "there" of our existence. We cry for the dead, a feeling of guilt about those endless forgotten dead, one after the other – 500-600 comrades in Sandi's book, my parents in mine – in this world. We read-converse-dance for those who have not crossed over because they have unfinished business with the living. The dead return as us either to claim that something should be done that wasn't, or because they have something more to say or to ask of the living. We honour the possibility of being dead for others. The dead as alliance of ethics and aesthetics of UNCOMMON GROUND. Whether summoning, authorizing, calling, making possible, inducing, inciting, enrolling, inviting, mobilizing, instructing, generating, claiming, regenerating, if not disturbing or prohibiting; or again, the particular practices of actions – dance, write, and more – that awaken certain forms of availability."

"All these verbs have the remarkable quality of leaving the question of the origin of the action totally open and indeterminate. This requires the capacity to hear other voices think in you and to translate events as intentions and to recognize, to discriminate, when that happens. It is a technique, and it is acquired. It is an expertise that lands when one realise that one chooses to listen deeper. The dead has to be installed, embedded. This is beyond the longing and mourning as I have written above. It is beyond a grave, a memorial service, a celebration of lives – once."

"We are finding an embodiment of our lives, a living shelter, keeping the dead alive, for ourselves. We are making space to infuse life in an extraordinary way, allowing other living beings to find their own living as dying-living. Composting. Answering to what the dead require. Taking ourselves through continual metamorphoses and give attention as a form of love to these difficulties of losing and finding ourselves continually to the world. Towards this we require a lowered intensity, a retraction of the will, an ecological attention as a form of love."

"Just a brief pause to tell the reader of my crepuscular (twilight) experiences of the senses. Unexpectable, and inconstructible, I often have the sense of the taste of my parents, in my mouth. It is a taste that marks their particular familiarness with something soulful and very particular to their bodies, zeitgeist, politics, milieu and ecology. It is faintly salty, something that rises between the remembering self and the remembered self, where no dismemberment could occur. I cannot evoke this phenomenon, and may it remain uncommon ground, for my memory to locate my senses irrevocably."

Enigma

"As in UNCOMMON GROUND the act of com-memoration through our books responds to a desire through dance where one can't decide if who we have become – and will leave as legacy – emanates from the person one remembers – such as figures in our books – or from the person writing, taking charge of the memory. It is a relationship of forces that an event has got going for it; the desire to be remembered and the desire to remember "hang" together; neither is prior. The same stands for our planet: we com-memorise a desire to remember, and we are remembered through, with and as our performing bodies. Everything exists as a tact of attention as a form of love: Our lives, artistic productions, the enlivening thereof as legacy, and the awakened senses as ontology of late earthly existence. I would advise these to be seen as enigma. This enigma is both key and guide. There is no desire to interpret. Yet there are affects, magnetic pulls, forces that traverse and direct us to the next move, instructing us to stay true to the narrative matrix of a history performing the present not linearly but radially, atmospherically. Any point in the books may give birth to any connection, any move of listened complexity which connives a newly patterned ecology. Some often feels like it throws me off-track, I want to cease all engagement, and as I sense: "the gods are not happy." Whichever way I am guided, I trust the intelligence that does so."

"There were no longer beginnings or ends. What exists and will exist would have a life form of its own which we would have abided by, and mostly directed, perhaps invented by myself, Sandi, and the dead. I radically impose an obedience constraint on myself, as I can be creative where creativity is not called for. Worse, to follow advice by people charged by emotion, alliances of race and politics, biases of ideologies, personal encounters, degrees of proximities and qualities of touch. UNCOMMON GROUND, which is embodying significant complex individual and collective activities, is beyond psycho-analysis, "unprocessed" matters of politics, relationship, race, whatever. It is the analogue of an enigmatic event, unfathomable, yet one of love. The way through, is the way as, a factor that enshrines complexity, diffraction, affect theory, Africanity, the body, praxes like Contact Improvisation, ancestral domaining, climate disaster, de-colonialism, restorative gardening, ritual, reading, writing (as now...) and honouring the dreambody ceaselessly. And, I am so open to try out new ideas on myself, such as new journalling devices, a laptop full of videos from my Crepuscular Genre (see on this archive) practice with Nicky Visser, each morning at 6 when we have not yet been troubleshot through with the world, money, family, work, leaking roofs and smelling carpets. Any word, when read to you, could make me jump or a simple sentence wrenches an emotion or sensation out of me. These have been my ecology since the time of writing. Neutrality does not rest by, and as, the reproduction of life. Complexity is too difficult to deal with on one's own."

In The End

"UNCOMMON GROUND could be seen as an artistic project with potential transformative powers, keeping the living and the dead together – the restless dead, the relentless living in elder bodies. Who are we to refuse? To show up for UNCOMMON GROUND is to show up for the dying world. What is motivating the living when it comes to the dead – from ecstasy to exorcism? The ancestors see, feel, think, ... everything. This is how I think ancestors materialise an event, with everything present and with a high degree of attention on everything. This fullness can also sometimes be overwhelming to the affective body, the one that erupts with thought, sensations, pulses, intensities, waves, itches, a sense of the mythology of the time and the role of this event within, catastrophes, lamentation, and unstoppable laughter at times."

"Pretend you are an ancestor and you need release from the world, and I/we will do the rest. The dead rises in every thought or action in the ontology of the performer. Things have to be done; the dead are endowed with an absolutely remarkable power to activate the living."

"But do not think that you solve every problem this way. One could also believe that the dead is dead. Then the answer to the question about our world: is it going to get better, or worse, is fait accompli. The dead never act in a direct manner. Just watch your mental order, and consider what is getting to you, what can get to you in some moment ‘to be lived.' The dead asks for us to pay attention, be on the alert, no matter the form or shape. It does not speak the future, it opens up possibles that still have to be lived, grasp things uncomfortably differently, socialise pain, staying with unknown trouble."

"All UNCOMMON GROUND does is witness the concern the dead have for the living, and show up for that vitality. And if UNCOMMON GROUND turns towards the powers of catastrophes, hopefully it is the birth of the revolution, yet again."

Joined here by Thalia Laric, proponent of Contact Improvisation in South Africa. 11 September 2025.